Sixty years ago, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was founded. The organisation grew out of widespread public concern about a frightening new twist in the Cold War arms race: Britain had built and was testing its own hydrogen bomb. Such H-bombs are thousands of times more destructive than the original atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945. How were the tests affecting the environment? Would the existence of such bombs mean the British government would feel compelled to use them?

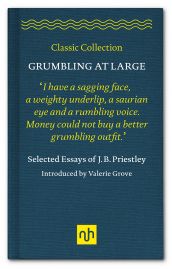

Deeply worried by these developments, celebrated author J.B. Priestley wrote possibly his most influential article: “Britain and the Nuclear Bombs”, published in the New Statesman of 2 November 1957.

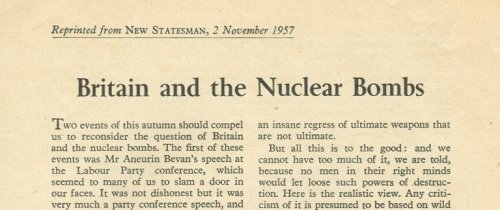

Section of Britain and the Nuclear Bombs, article by JB Priestley, New Statesman 2 November 1957. (ref HAW 13/4).

Priestley drew on his own experience of war to argue that if weapons were there, they would be used, and called for the country to take a moral lead in renouncing them: “Alone we defied Hitler; and alone we can defy this nuclear madness”.

Many readers agreed, and wrote to the magazine, overwhelming it with sackfuls of mail. Something had to be done. Priestley and his wife Jacquetta Hawkes met peace campaigners at the flat of Kingsley Martin, the magazine’s editor, to discuss a national anti-nuclear campaign. The result was the creation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. It was chaired by Earl Russell, Priestley was Vice-President and Canon L. John Collins chairman. Priestley was one of the speakers at the public launch of CND in the Central Hall Westminster, on 17 February 1958.

CND acted as an umbrella group, bringing together people with a wide range of political and religious views and differing ideas about how to achieve their goals (or even what those goals were). Priestley and Jacquetta and their circle were not necessarily pacifists, and campaigned using traditional lobbying methods, using their connections in political and cultural life. Other campaigners were veterans of the Peace Pledge Union era, while others were influenced by Gandhian ideas of nonviolent direct action. The latter included the Direct Action Committee (DAC), whose members had explored the potential of such techniques as long ago as the early 1950s.

The DAC organised a march from London to the Aldermaston weapons research centre for Easter 1958. Graphic designer Gerald Holtom created the Nuclear Disarmament Symbol for use on the march. CND later adopted both the design and the Aldermaston march.

Detail from sketch by Gerald Holtom, showing the nuclear disarmament symbol in use on a march. Courtesy of Commonweal Trustees. (ref: Cwl ND).

The Symbol was based on the semaphore signs for ‘N’ and ‘D’ but in its simplicity it echoed many other ideas: a human figure in despair, a tree, a cross, a missile. Endlessly applicable to creative re-imaginings, and adopted by Americans protesting against the Vietnam War, the Symbol became synonymous with peace and counter-cultural ideas.

CND in its early years grew a mass membership and was strongly influential on culture. Members moved increasingly towards direct action methods as traditional campaigning did not have the desired result. In 1960 Russell resigned as President to take up a role in the new Committee of 100. This aimed to create a mass movement of civil disobedience against British government policy on nuclear weapons. The Priestleys became less involved as the group became more radical.

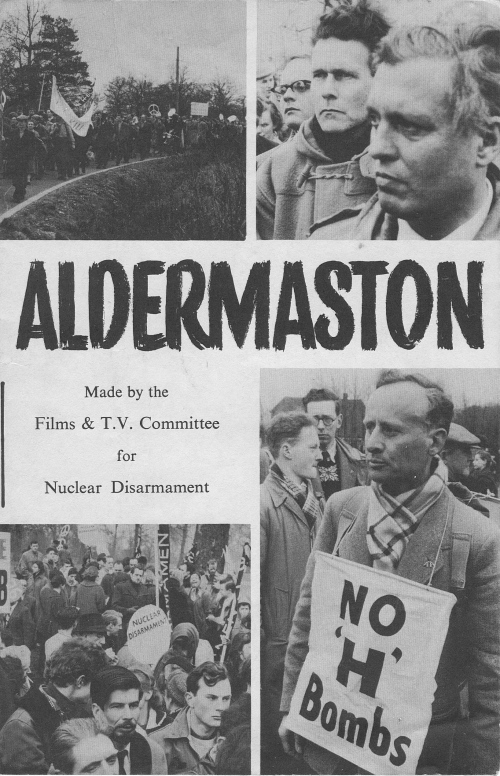

Front cover of pamphlet advertising Aldermaston film (ref Cwl HBP)

The organisation, and its many regional and themed sub-groups, has remained active ever since its foundation, with a notable rise in membership and influence once again during the early 1980s. Protest centred on the peace camps at air bases: bearing witness, symbolic protest, and carrying out acts of disobedience such as cutting the wires.

The 60th anniversary will be marked by many events (and no doubt much press coverage). Here are two in Bradford:

Yorkshire CND exhibition at the Peace Museum from 12 January 2018.

CND 60th Anniversary event 17 February 2018 (includes the chance to meet objects from our collections!).

Want to know more? The Commonweal Library and our peace campaign collections contain thousands of resources for the history of CND and nuclear disarmament campaigns.